Organic and, in later stages, mechanical damage to retinal tissue, leading to pronounced specific impairments of visual functions, is collectively called retinopathy. What is common in the group of primary (independent) and secondary (developing as a result of other diseases) retinopathy is that their etiopathogenetic basis is made up of progressive disorders in the choroid that feeds the retina, the so-called. angiopathy, which results in a constant lack of blood supply, and consequently, hypoxia and lack of nutrients necessary for the normal functioning of the tissue.

Distinctions between retinopathy of one type or another are made mainly according to the criterion of the original cause of vascular disorders. Thus, they distinguish traumatic and diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, etc. One of the most widespread variants is hypertensive retinopathy, caused by arterial hypertension syndrome - chronically high blood pressure. A distinctive feature of this form of retinal damage is the tendency to hemorrhages (hemorrhages) and accumulations of exudative fluid in the tissues of the fundus, which leads to their swelling and, in more serious cases, to swelling of the optic nerve head.

Classification

Retinopathy is a very dangerous condition, which, without proper treatment, leads to irreversible disorders of the blood supply, hypoxia and atrophy of the visual organs. Secondary pathologies account for a greater number of cases, since many chronic diseases are burdened with this kind of complications.

The following types of background retinopathy are distinguished:

- hypertensive;

- diabetic;

- atherosclerotic;

- hematological;

- post-traumatic.

| Background retinopathy of any nature develops in several stages. It is very important to identify the disease at an early stage in order to prevent further development of pathogenesis and restore lost vision. |

Hypertensive retinopathy

Background retinopathy of this type develops as a consequence of stable arterial hypertension. Constant hypertension causes destructive changes in the vascular bed, which, in turn, provoke interruptions in the circulatory systems, metabolism, etc. The organs and tissues of the body face a deficiency of oxygen and other substances, which negatively affects their functionality. From an ophthalmological point of view, the retina of the eye suffers first of all, since its structure contains many capillaries.

There are 4 stages of the disease:

- Angiopathy.

The initial period of the disease, in which vasospasms of the retinal vessels occur, causing a narrowing of the diameter of the alveoli and focal thickening/dilation of the veins. In this case, single arteriovenous intersections are formed, in which the arteriole presses the vein at the intersection point. At this stage, the processes are still reversible and do not have a significant negative effect on the visual organ.

- Angiosclerosis.

Pathogenesis takes on an organic character. The vessels of the retina become thinner and deformed at the points of crossover, which become much more numerous. In this case, an expanded light reflex and obliteration in areas of arterioles and veins are observed.

- Hypertensive retinopathy.

Vascular lesions affect adjacent areas, numerous hemorrhages and plasmorrhages appear. Lipids and protein transudate accumulate in the posterior sections of the vitreum. Due to damage to nerve endings, zones of ischemic infarction are formed.

- Neuroretinopathy.

At this stage, irreversible sclerotic damage to the vascular bed inevitably causes papilledema. Necrotic retinal detachment occurs, leading to complete atrophy of the eyeball.

Background retinopathy in hypertensive patients is detected more often after 40 years of age and older. However, age is not the only prerequisite for the occurrence of arterial hypertension. At risk are people suffering from obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and kidney and adrenal gland disorders. In addition, those who abuse alcohol, eat foods high in salt, smoke, and lead a passive lifestyle are prone to hypertension and its complications. Hypertensive disorders are also characteristic of acute toxicosis in pregnant women.

Stages of hypertensive retinopathy

In the development of hypertensive retinopathy, four main stages are logically distinguished:

- stage of hypertensive angiopathy - initial, purely functional and at this stage still reversible disorders in the choroid associated with the retina;

- angiosclerosis - organic degeneration of the tissues of the vascular walls, a gradual decrease in elasticity and capacity due to the larger volume of connective tissue compared to the working functional tissue, and also (in some cases) due to cholesterol deposits in the retinal vessels;

- the retinopathic stage itself - due to the pathologically increased permeability of the vascular walls, the tissues underneath them become saturated with effusion, patches of hemorrhagic swelling, opacities appear, as well as dystrophic and degenerative changes in the macular zone (i.e. in the central, most photosensitive “yellow spot” of the retina) caused by constant ischemia - lack of blood supply;

- hypertensive neuroretinopathy - swelling becomes chronic and spreads to the layers around the optic nerve, as well as to the optic disc itself, where degenerative changes develop. At this stage, there is a significant deterioration in vision and a narrowing of its fields; If you do not take active therapeutic measures, the prognosis becomes less and less favorable - optic nerve atrophy, retinal detachment and, as a consequence, irreversible loss of vision.

Diabetic retinopathy

The cause of this type of ophthalmic disorder is diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2. Background retinopathy of this kind is observed in most diabetics, so its early diagnosis and treatment is of utmost importance.

The history of the disease is divided into three stages: non-proliferative, pre-proliferative and proliferative. The first two stages are characterized mainly by the same processes as during the angiopathic, atherosclerotic periods of hypertensive retinopathy.

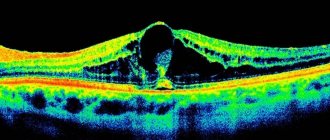

The proliferative stage is expressed in the appearance of many abnormal vessels throughout the retina and adjacent ocular structures. These tumors are very fragile and often bleed. Hemorrhages enter the vitreous body, provoking subtotal hemophthalmos, ultimately leading to partial or complete destruction of the vitreum and detachment of the retina.

The processes of diabetic eye damage progress rapidly and are often detected in the later stages of the disease. Diabetics should be regularly observed by an ophthalmologist in order to detect pathology in time and undergo the necessary course of treatment.

Treatment of hypertensive retinopathy

From the above, it clearly follows that therapeutic success in the treatment or compensation of hypertensive retinopathy depends critically on the severity of organic changes in the vessels and tissues of the retina, i.e. from the stage at which treatment begins. As a rule, the first therapeutic measures are conservative: drugs with vasodilating and angioprotective effects, anticoagulants, vitamin complexes, as well as oxygen barotherapy are prescribed to saturate the tissues with the missing oxygen. Needless to say, therapeutic control of the underlying disease is of great importance, i.e. arterial hypertension.

At later stages, if there is a risk of retinal detachment, laser coagulation may be required; in the final stages, with deep organic degradation, it is sometimes necessary to resort to ophthalmic surgery.

Advantages of our ophthalmology center:

- The latest equipment from world manufacturers allows you to make an accurate diagnosis and carry out effective treatment.

- Leading retina specialists in Moscow: retinologists, laser and vitreoretinal surgeons.

- Individual approach to each patient, affordable prices and a guarantee of high treatment results!

Thus, when the symptoms described above appear (or when the ophthalmologist identifies the first signs of hypertensive retinopathy), delaying treatment means playing a very dangerous game with quickly passing time, where the stake is your own vision. A missed opportunity to stop or at least slow down the pathological process can result in complete blindness. Therefore, for people at risk or with clinically established hypertensive retinopathy, regular observation by an ophthalmologist and scrupulous compliance with his instructions is strictly mandatory.

Atherosclerotic retinopathy

Ophthalmological pathology is caused by atherosclerosis - a decrease in the capacity of blood vessels due to the formation of lipid plaques on their inner walls. The disease can affect any vessels, including the eye vessels, causing their pathological deformation and hypoxia. Such background retinopathy is not uncommon in people with high cholesterol levels in the blood, those who are overweight, diabetes mellitus, and those who are addicted to smoking and alcohol.

The stages of development of the pathology in their characteristics correspond to the hypertensive form, however, in the last stages, atherosclerotic deposits on the periphery of the retina, numerous hemorrhages, and blanching of the optic disc are often diagnosed.

Manifestations of arterial hypertension in the fundus

The vessels of the retina, choroid and optic nerve have differences in structure. This explains the variety of manifestations of arterial hypertension in the fundus.

Changes in arteriolar lumen diameter are an essential component of the regulation of systemic blood pressure levels. Thus, a 50% decrease in lumen leads to a 16-fold increase in blood pressure. If a change in the caliber of blood vessels is associated only with an increase in blood pressure, then after its normalization, the fundus picture returns to normal. Atherosclerotic changes in the walls of blood vessels can also play a role - in this case, changes in the fundus are irreversible. For this reason, the first symptom to judge the presence of arterial hypertension is a change in the caliber of blood vessels. The normal artery/vein thickness ratio is 2/3. When blood pressure rises, as a rule, arterioles begin to narrow and veins begin to expand. These changes may be uneven throughout the same vessel.

When the vessels of the fundus of the eye are damaged by atherosclerosis, characteristic manifestations are determined, such as the symptom of “copper” and “silver wire”. Normally, along the lumen of the vessel during ophthalmoscopy, a light reflex is visible, which is formed due to the reflection of light from the column of blood in it. As the walls thicken and sclerose, light begins to be reflected from them, as a result of which the reflex becomes wider and less bright, acquires a brown tint (hence the “copper wire” symptom), and if the process progresses, it becomes whitish (the “silver wire” symptom).

The symptom of arteriovenous decussation, or the Salus-Gunn symptom, is considered the most pathognomonic for arterial hypertension. It is caused by sclerosis of the walls of the arteriole, as a result of which its thickened wall reflects light more strongly, shading the underlying vein.

There are three degrees: Salus I - compression of the vein at the intersection with the artery. The vein is thinned on both sides, conically narrowed. Salus II - the same picture is visible as with Salus I, but the vein bends before the cross to form an arch. Salus III - the vein under the artery at the intersection and not visible at the edges of the intersection; it is thinned, curved and, near the intersection, expanded due to a violation of the outflow of venous blood. The vein is deeply pressed into the retina.

The next sign of increased blood pressure is a violation of the normal branching of blood vessels. Normally, they diverge at an acute angle, and in the presence of hypertension, this angle can even reach 180 degrees (symptom of “tulip” or “bull horns”). Elongation and tortuosity of the vessels may also be observed. The Gwist sign or “corkscrew” sign is the increased tortuosity of the venules in the macular zone.

Retinal hemorrhages are more serious in terms of prognosis for life. They arise due to the penetration of red blood cells through the altered vascular wall, its rupture due to increased blood pressure or due to previous microthrombosis. Most often, hemorrhages occur near the optic disc in the layer of nerve fibers and have the appearance of radially diverging stripes or streaks. In the macular area, hemorrhages resemble a star figure.

Impaired retinal nutrition in hypertension can lead to infarctions of small areas of nerve fibers, which entails the appearance of cotton wool-like, “soft” exudates. “Hard” exudates are less pathognomonic for arterial hypertension, but, nevertheless, can be detected in this disease. They can be pointy or large, round or irregular in shape; in the macular zone they often form a star shape.

Swelling of the retina and optic disc is determined in severe arterial hypertension and often accompanies the above-described changes in the fundus.

Also, a consequence of increased blood pressure can be occlusions and thromboses of the retinal vessels.

In rare cases, changes can be observed in the choroid of the eye: Elshing spots - dark spots surrounded by a light yellow or red halo; Siegrist stripes – linear hyperpigmented spots along the choroidal vessels; exudative retinal detachment. Their cause is a violation of microcirculation in this membrane of the eye in severe arterial hypertension.

The degree and duration of arterial hypertension often, but not always, determine the severity of changes in the fundus. In some cases, against the background of increased blood pressure, signs of damage to the retinal vessels are not detected, while in others, on the contrary, the picture of the fundus indicates severe damage to the internal organs, despite compensated pressure. The identified changes in the retina are not specific only to arterial hypertension. Various conditions may be associated with hypertensive retinopathy: ethnicity, smoking, increased intima-media thickness and plaque in the carotid artery, decreased elasticity, increased blood cholesterol, diabetes, increased body mass index.

Some changes tend to spontaneously resolve after normalization or stabilization of blood pressure, and therefore the picture of the fundus after some time can be strikingly different in one patient. To a greater extent, this applies to the initial stages of hypertension. Studies have shown that, even without taking into account the individual characteristics of the structure of the vascular tree of each person, the width and tortuosity of the vessels can vary even within one day. The caliber can change throughout one vessel and is also not constant. From the above, it is easy to conclude that this variability, as well as the method of examination, and the qualifications of the ophthalmologist who examined the fundus, lead to a significant discrepancy in medical reports. This fact is supported by data from one study that assessed interrater agreement in assessing microvascular changes. Thus, it was lowest when assessing arteriolar narrowing, and higher when assessing the symptoms of chiasm (Salus-Gunn symptom). Opinions most often coincided when identifying hemorrhages and exudates.

Studies have shown a low prevalence of retinal changes in patients with hypertension (3-21%). Half of people without signs of hypertensive retinopathy suffered from high blood pressure. However, changes in the fundus were rarely found in healthy people (specificity - 88-98%). Narrowing of arterioles in 32-59% indicated hypertension, the presence of the Salus-Hun symptom - in 44-66%. Moreover, the latter can also be detected both in people with arterial hypertension and in healthy people or with age-related changes. The occurrence of Gwist's symptom in patients with increased blood pressure, according to various authors, ranges from 10 to 55% of cases.

The presence of hemorrhages and exudates in the fundus in 43-67% indicated arterial hypertension. At the same time, in the Beaver Dam eye study and the Blue Mountains eye study, there were no significant differences in the frequency of detection of hemorrhages and exudates in patients with normal and high blood pressure over the age of 65 years.

Retinopathy in blood diseases

Pathology occurs against the background of anemia, leukemia, myeloma, excessive myeloproliferation. The clinical picture may vary, but the essence of ophthalmological disorders will be the same.

Background retinopathy in anemia is not common. However, with chronic hemoglobin deficiency, for example, the pernicious form, optical neuropathy is observed with the formation of scotomas, hemorrhages, and cotton wool-like lesions along the periphery of the retina. The color of the fundus can range from pale to bluish. Peripapillary edema may develop.

Retinopathy against the background of leukemia develops more often and is expressed by persistent pathological processes leading to vascular tortuosity, thinning of the iris, formation of hemophthalmos, and optic neuropathy.

Multiple myeloma is associated with increased blood viscosity resulting from polycythemia. Background rhitinopathy is expressed in the expansion of veins, the formation of blood clots, the occurrence of hemorrhages and microaneurysms.

Treatment of background retinopathy in hematological disorders depends on the specific disease and is aimed at suppressing ophthalmic pathogenesis and stabilizing visual function.

Stages of the disease

According to the existing classification, hypertensive retinopathy in its development goes through 4 stages:

Angiopathy is the first stage, occurring with functional changes that affect the retinal vessels and are reversible.

Angiosclerosis is the second stage, characterized by organic changes in the retinal vessels of a reversible nature.

Retinopathy is the third stage with pathological foci around altered retinal vessels. It is characterized by the occurrence of hemorrhages, focal opacities, degenerative lesions of its central part, often with the presence of a “star” or “half-star” pattern.

Neuroretinopathy is the fourth stage, which, with existing manifestations of angiopathy, angiosclerosis, retinopathy, is complicated by swelling of the optic disc and clouding of the retina over it. This leads to a significant decrease in visual acuity and narrowing of its fields.

Post-traumatic retinopathy

Injury can also lead to retinopathy. The disease develops as a result of sudden great pressure on the eyes (impact, radiation) or against the background of an ischemic condition provoked by a narrowing of the arteries of the spine and sternum (skull injuries, fractures, concussion, etc.).

The result of such injuries is a sharp decrease in blood supply to the retina and oxygen deficiency. The situation is complicated by hemorrhages, swelling of the inner layers of the retina, and clouding of the transparent ocular structures. If the underlying retinopathy is not treated, atrophic lesions cannot be avoided.

Fundus changes in hypertension

Nesterov AP The article consists of the lecture for physicians and ophthalmologists. Symptoms of functional changes in the central retinal vessels, features of hypertonic angiosclerosis of retinal vessels, peculiarities of hypertonic retinopathy and neuroretinopathy are discussed in the article and recommendations for treatment of the hypertonic retinopathy are given.

The frequency of fundus lesions in patients with essential hypertension (HD), according to various authors, varies from 50 to 95% [1]. This difference is caused partly by age and clinical differences in the patient population studied, but mainly by the difficulty of interpreting the initial changes in the retinal vessels in hypertension. Internists attach great importance to such changes in the early diagnosis of hypertension, determining its stage and phase, as well as the effectiveness of the therapy. The most interesting in this regard are the studies of R. Salus. In a well-organized experiment, he showed that the diagnosis of headache, made by him based on the results of ophthalmoscopy, turned out to be correct only in 70% of cases. Misdiagnosis is associated with significant interindividual variation in retinal vessels in healthy individuals, and some of the variations (relatively narrow arteries, increased vascular tortuosity, crossover sign) may be misinterpreted as hypertensive changes. According to the observations of O.I. Shershevskaya [7], during a single check of an unselected contingent of HD patients, specific changes in the retinal vessels are not detected in 25–30% of them in the functional period of the disease and in 5–10% in the late phase of the disease. Vessels of the retina and optic nerve The central retinal artery (CRA) in its orbital section has a structure typical of medium-sized arteries. After passing through the cribriform plate of the sclera, the thickness of the vascular wall is halved due to thinning (from 20 to 10 µm) of all its layers. Within the eye, the CAS is repeatedly divided dichotomously. Starting from the second bifurcation, the branches of the CAS lose their inherent characteristics of arteries and turn into arterioles. The intraocular part of the optic nerve is supplied mainly (with the exception of the neuroretinal layer of the optic disc) from the posterior ciliary arteries. Posterior to the lamina cribrosa of the sclera, the optic nerve is supplied by centrifugal arterial branches originating from the CAS and centropetal vessels originating from the ophthalmic artery. The capillaries of the retina and optic disc have a lumen with a diameter of about 5 µm. They start from precapillary arterioles and connect to venules. The endothelium of the capillaries of the retina and optic nerve forms a continuous layer with tight junctions between cells. Retinal capillaries also have intramural pericytes, which are involved in the regulation of blood flow. The only blood collector for both the retina and the optic disc is the central retinal vein (CRV). The adverse effects of various factors on retinal blood circulation are smoothed out due to vascular autoregulation, which ensures optimal blood flow using local vascular mechanisms. This blood flow ensures the normal course of metabolic processes in the retina and optic nerve. Pathomorphology of retinal vessels in HD Pathomorphological changes in the initial transient stage of the disease consist of hypertrophy of the muscle layer and elastic structures in small arteries and arterioles. Stable arterial hypertension leads to hypoxia, endothelial dysfunction, plasmatic saturation of the vascular wall with subsequent hyalinosis and arteriolosclerosis [3]. In severe cases, fibrinoid necrosis of arterioles is accompanied by thrombosis, hemorrhages and microinfarctions of retinal tissue. Retinal vessels in hypertension Two vascular trees are clearly visible in the fundus: arterial and venous. It is necessary to distinguish: (1) the severity of each of them, (2) the characteristics of branching, (3) the ratio of the caliber of arteries and veins, (4) the degree of tortuosity of individual branches, (5) the nature of the light reflex on the arteries. The severity and richness of the arterial tree depend on the intensity of blood flow in the central nervous system, refraction and the condition of the vascular wall. The more intense the blood flow, the better the small arterial branches are visible and the more branched the vascular tree. With hypermetropia, the retinal vessels appear wider and brighter during ophthalmoscopy than with emmetropia, and with myopia they become paler. Age-related thickening of the vascular wall makes small branches less noticeable, and the arterial tree of the fundus in elderly people looks depleted. With hypertension, the arterial tree often looks poor due to tonic contraction of the arteries and sclerotic changes in their walls. Venous vessels, on the contrary, often become more pronounced and acquire a darker, more saturated color (Fig. 4, 1, 5). It should be noted that in some cases, provided that the elasticity of the blood vessels is preserved, patients with hypertension experience not only venous, but also arterial congestion. Changes in the arterial and venous vascular beds also manifest themselves in changes in the arteriovenous ratio of retinal vessels. Normally, this ratio is approximately 2:3; in patients with hypertension it often decreases due to narrowing of the arteries and dilation of the veins (Fig. 1, 2, 5). Narrowing of retinal arterioles in hypertension is not a necessary symptom. According to our observations [3], pronounced narrowing, which can be determined clinically, occurs only in half of the cases. Often only individual arterioles narrow (Fig. 2, 5). The unevenness of this symptom is characteristic. It is manifested by asymmetry of the state of the arteries in paired eyes, narrowing of only individual vascular branches, and uneven caliber of the same vessel. In the functional phase of the disease, these symptoms are caused by unequal tonic contraction of the vessels, in the sclerotic phase - by uneven thickening of their walls. Much less often than narrowing of the arteries, with hypertension, their dilation is observed. Sometimes both narrowing and dilation of arteries and veins can be seen in the same eye and even on the same vessel. In the latter case, the artery takes on the appearance of an uneven chain with swellings and interceptions (Fig. 5, 7, 9). One of the common symptoms of hypertensive angiopathy is disruption of the normal branching of the retinal arteries. Typically, the arteries branch dichotomously at an acute angle. Under the influence of increased pulse beats in hypertensive patients, this angle tends to increase, and it is often possible to see branching of the arteries at right or even obtuse angles (“bull horns symptom”, Fig. 3). The greater the branching angle, the greater the resistance to blood movement in this zone, the stronger the tendency to sclerotic changes, thrombosis and disruption of the integrity of the vascular wall. High blood pressure and large pulse amplitude are accompanied by an increase in not only lateral, but also longitudinal stretching of the vascular wall, which leads to lengthening and tortuosity of the vessel (Fig. 5, 7, 9). In 10–20% of patients with hypertension, tortuosity of the perimacular venules is also observed (Gwist's sign). The Hun–Salus intersection symptom is essential for the diagnosis of fundus hypertonicity. The essence of the symptom is that at the point of intersection of the venous vessel with a condensed artery, partial compression of the latter occurs. There are three clinical grades of this symptom (Fig. 4). The first degree is characterized by a narrowing of the lumen of the vein under the artery and near the intersection of the vessels. A feature of the second degree is not only partial compression of the vein, but also its displacement to the side and into the thickness of the retina (“arch symptom”). The third degree of vascular decussation is also characterized by an arch symptom, but the vein under the artery is not visible and seems completely compressed. The symptom of decussation and venous compression is one of the most common in hypertension. However, this symptom can also be found in retinal arteriosclerosis without vascular hypertension. Symptoms pathognomonic for retinal arteriosclerosis in hypertension include the appearance of side stripes (“cases”) along the vessel, symptoms of “copper” and “silver” wire (Fig. 5). The appearance of white lateral stripes is explained by thickening and decreased transparency of the vascular wall. The stripes are visible along the edge of the vessel, since there is a thicker layer of the wall and a thinner layer of blood compared to the central part of the vessel. At the same time, the light reflex from the front surface of the vessel becomes wider and less bright. The symptoms of copper and silver wire (the terms were proposed by M. Gunn in 1898) are interpreted ambiguously by various authors. We adhere to the following description of these symptoms. The copper wire symptom is found mainly on large branches and is characterized by an expanded light reflex with a yellowish tint. The symptom indicates sclerotic changes in the vessel with a predominance of elastic hypertrophy or plasmatic impregnation of the vascular wall with lipoid deposits. The silver wire symptom appears on arterioles of the second or third order: the vessel is narrow, pale, with a bright white axial reflex, often it seems completely empty. Retinal hemorrhages Hemorrhages in the retina during hypertension occur by diapedesis of red blood cells through the altered wall of microvessels, rupture of microaneurysms and small vessels under the influence of increased pressure or as a consequence of microthrombosis. Especially often, hemorrhages occur in the layer of nerve fibers near the optic disc. In such cases, they look like radially arranged strokes, stripes or flames (Fig. 9). In the macular zone, hemorrhages are located in the Genly layer and have a radial location. Much less often, hemorrhages are found in the outer and inner plexiform layers in the form of irregularly shaped spots. Retinal “exudates” Hypertension is especially characterized by the appearance of soft exudates resembling cotton wool. These grayish-white, loose-looking, anteriorly protruding lesions appear predominantly in the parapapillary and paramacular zones (Fig. 8, 9). They arise quickly, reach maximum development within a few days, but never merge with each other. During resorption, the focus gradually decreases in size, flattens and fragments. Cotton wool lesion is an infarction of a small area of nerve fibers caused by microvascular occlusion [8, 9]. As a result of the blockade, axoplasmic transport is disrupted, nerve fibers swell, and then fragment and disintegrate [10]. It should be noted that such lesions are not pathognomonic for hypertensive retinopathy and can be observed with congestive discs, diabetic retinopathy, CVS occlusion, and some other retinal lesions in which necrotic processes develop in the arterioles. Unlike cotton wool-shaped lesions, hard exudates in hypertension have no prognostic value. They can be dotted or larger, round or irregular in shape (Fig. 7, 8), located in the outer plexiform layer and consist of lipids, fibrin, cellular debris and macrophages. It is believed that these deposits arise as a result of the release of plasma from small vessels and subsequent degeneration of tissue elements. In the macular region, solid lesions have a banded shape and a radial arrangement, forming a complete or incomplete star figure (Fig. 8, 9). They have the same structure as other solid lesions. As the patient's condition improves, the star's figure may dissolve, but this process takes a long time - over several months or even several years. Swelling of the retina and optic disc Swelling of the retina and optic disc, combined with the appearance of soft lesions, indicates a severe course of hypertension (Fig. 7, 9). Edema is localized mainly in the peripapillary zone and along the course of large vessels. With a high content of proteins in the transudate, the retina loses transparency, becomes grayish-white and the vessels are covered in places with edematous tissue. Swelling of the optic disc can be expressed to varying degrees - from slight blurring of its contour to a picture of a developed stagnant disc. Congestive disk in hypertension is often combined with peripapillary retinal edema, retinal hemorrhages and cotton wool lesions (Fig. 9). Visual functions Decreased dark adaptation is one of the earliest functional signs in hypertensive retinopathy [5]. At the same time, there is a moderate narrowing of the isopter and the boundaries of the visual field, as well as an expansion of the “blind spot”. With severe retinopathy, scotomas localized in the paracentral region of the visual field can be detected. Visual acuity decreases much less frequently: with ischemic maculopathy, macular hemorrhages, with the occurrence of edematous maculopathy and with the formation of the epiretinal membrane in the late stage of neuroretinopathy. Classification of hypertensive changes in the fundus Currently, there is no generally accepted classification of hypertensive angioretinopathy. In Russia and neighboring countries (former republics of the USSR), the most popular classification is M.L. Krasnov and its modifications. M.L. Krasnov [4] identified three stages of fundus changes in hypertension: 1. hypertensive angiopathy, characterized only by functional changes in the retinal vessels; 2. hypertensive angiosclerosis; 3. hypertensive retino- and neuroretinopathy, which affects not only the vessels, but also the retinal tissue, and often the optic disc. The author divided retinopathy into 3 subgroups: sclerotic, renal and malignant. The most severe changes in the retina are observed in renal and especially malignant forms of headache (Fig. 9). The stages of hypertension and the prognosis for the patient’s life are determined by the height of blood pressure and the severity of vascular changes in the kidneys, heart and brain. These changes are not always parallel with retinal lesions, but there is still a certain relationship between them. Therefore, multiple hemorrhages in the retina, the appearance of areas of ischemia, non-perfused zones, cotton-wool exudates, as well as pronounced swelling of the optic disc and peripapillary retina indicate the severe progressive nature of the disease and the need to change and intensify therapeutic measures. Treatment of hypertensive neuroretinopathy Therapy of hypertensive (neuro)retinopathy consists of treating the underlying disease. To reduce retinal ischemia, vasodilators are used, which dilate mainly the vessels of the brain and eye (Trental, Cavinton, Xavin, Stugeron). Oxygen inhalation is often used to reduce hypoxia. However, oxygen can cause retinal vasoconstriction [6]. Therefore, we prefer to prescribe carbogen inhalations, which in addition to oxygen contains carbon dioxide (5–8%). Carbon dioxide has a strong vasodilatory effect on the vessels of the brain and eyes. To improve blood rheology and prevent the occurrence of thrombosis, antiplatelet agents are used. It should be taken into account that elimination of retinal ischemia can lead to the development of post-ischemic reperfusion syndrome, which consists of excessive activation of free radical processes and lipid peroxidation. Therefore, constant intake of antioxidants (alpha-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, veton, diquertin) is essential. The use of angioprotectors, especially doxium, is useful. Preparations containing proteolytic enzymes (Wobenzym, papain, recombinant prourokinase) are used to resolve intraocular hemorrhages. For the treatment of retinopathy of various origins, transpupillary irradiation of the retina using a low-energy infrared diode laser is prescribed.

Literature 1. Vilenkina A.Ya. // Collection of materials from NIIGB im. Helmholtz. – M., 1954. – P. 114–117. 2. Katsnelson L.A., Forofonova T.I., Bunin A.Ya. // Vascular diseases of the eye. – M. 1990. 3. Komarov F.I., Nesterov A.P., Margolis M.G., Brovkina A.F. // Pathology of the organ of vision in common diseases. – M. 1982. 4. Krasnov M.L. // Vestn. ophthalmol. – 1948. – No. 4., pp. 3–8. 5. Rokitskaya L.V. // Vestn. ophthalmol. – 1957. – No. 2. – P. 30–36. 6. Sidorenko E.I., Pryakhina N.P., Todrina Zh.M. // Physiology and pathology of intraocular pressure. – M. 1980. – P. 136–138. 7. Shershevskaya O.I. // Eye damage in some cardiovascular diseases. – M. 1964. 8. Harry J., Ashton N. // Trans. Ophthalmol. Soc. UK. – 1963. – V. 83. – P. 71–80. 9. McLeod D. // Brit. J. Ophthalmol. – 1976. – V. – 60. – 551–556. 10. Walsh JB // Ophthalmology. – 1982. – V. – 89. – P. 1127–1131.

Symptoms

The clinical picture for any type of secondary retinopathy is determined by similar signs that are not noticeable in the initial stages.

However, progressive pathogenesis makes itself felt:

- periods of photopsia;

- incorrect color perception;

- decreased contrast;

- decreased visual acuity (farsightedness in diabetics);

- the appearance of moving dots, spots, patterns;

- hemophthalmos.

If you have any visual disturbances, you should immediately consult a doctor. Treatment of underlying retinopathy cannot be delayed.

Diagnostics

There are many ways to diagnose the disease, identify the features of its development and the degree of damage.

Typically, the following types of diagnostic tests are used:

- perimetry, visometry;

- direct/indirect ophthalmoscopy;

- Ultrasound;

- biomicroscopy;

- angiography;

- MRI;

- electroretinography.

Diagnosis is carried out not only by an ophthalmologist, but also by other specialists in order to identify the root causes and prescribe appropriate treatment for underlying retinopathy.

Treatment

The therapeutic program includes several areas depending on the severity of the patient’s condition. Drug treatment of background retinopathy involves taking drugs that minimize the pathological effect of the underlying disease and suppress the progressive pathogenesis of ophthalmic disorders (angioprotectors, antioxidants, vitamins, vasoactivators).

In most cases, drug therapy does not lead to a cure on its own, so more effective methods are used - laser coagulation and surgery. Laser treatment of background retinopathy gives positive results, especially in the initial stages of the disease. The procedure allows you to localize areas of neovascularization, “seal” damaged vessels, and prevent detachment of the retina. Coagulation is carried out in several sessions depending on the severity of symptoms.

If medication and other types of therapy are ineffective, ophthalmic surgery is performed. Vitrectomy surgery is a radical method that involves removing the affected part or the entire mass of the vitreous and replacing it with an artificial graft. This surgery allows you to restore lost vision to its original parameters.

Timely detection and treatment of background retinopathy allows one to avoid severe consequences and preserve vision, despite concomitant pathologies.

Making an appointment Today: 17 registered

Organ of vision in arterial hypertension

Description

Currently, arterial hypertension is one of the leading problems of modern medicine, which is due not only to the widespread prevalence of the disease, but also to the place it occupies in the structure of mortality. In economically developed countries, increased blood pressure is observed in 15%

of the adult population and in approximately

30-40%

of patients, arterial hypertension occurs latently. In recent years, the incidence of arterial hypertension, including in young people, has been increasing.

The upper limit of normal blood pressure in adults is considered to be 159/94

mmHg Art.

In modern cardiology, two types of increased blood pressure are distinguished: hypertension and symptomatic arterial hypertension.

The term “hypertension” was proposed by G. F. Lang in 1922. The work of Soviet cardiologists made it possible to consider hypertension as an independent nosological form. In 1962, the WHO Expert Committee recognized the concept of “essential hypertension”, adopted abroad, and the concept of “hypertension”, common in domestic medicine, as identical.

Currently, the neurogenic theory of the origin of hypertension has received the most recognition. It is believed that neurosis occurs due to overstrain of the basic nervous processes. Subsequently, stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system causes vasospasm, increased nervous activity, and activation of the renal factor. In the later stages of the disease, organic damage to the arterioles appears in the form of arteriosclerosis, which maintains the presence of arterial hypertension.

Hypertension accounts for 75—80%

cases of increased blood pressure. The clinical course of the disease is divided into three stages. All of them are usually characterized by slow chronic progression with an overall benign assessment of the course of the disease. Depending on the characteristics of the clinic and the severity of vascular lesions, it is customary to distinguish certain forms of clinical course. At any stage of hypertension, a clinical variant of its malignant course is possible.

Symptomatic arterial hypertension is caused by pathology of various organs and tissues. It is one of the symptoms, often leading, along with other clinical manifestations of the disease. Symptomatic arterial hypertension occurs in 20—25%

cases of hypertensive conditions.

The variety of forms of symptomatic hypertension (about 50

) is due to the fact that diseases of many organs and systems of the body can lead to an increase in blood pressure.

Among symptomatic hypertension, the most common is renal (50%

), caused by damage to the kidneys and renal arteries. And among kidney diseases, chronic glomerulonephritis ranks first as a cause of increased blood pressure. This also includes kidney damage of a similar nature that develops in the second half of pregnancy - pregnancy nephropathy.

Chronic pyelonephritis and renal artery occlusion often lead to increased blood pressure. According to the most common repopressor theory, renal hypertension owes its origin primarily to ischemia of the renal tissue and the formation of pressor substances Tina repin - angiotensin.

There are a large number of other primary diseases, different in nature, that in one way or another lead to increased blood pressure. These include, in particular, diseases of the endocrine glands, nervous system, lesions of large arterial trunks, atherosclerosis of the aorta, and blood diseases.

An essential place in the study of many aspects of the pathogenesis, clinical picture, and prognosis of arterial hypertension belongs to the organ of vision, and ophthalmoscopy is of invaluable importance. The history of these studies dates back to the middle of the last century and is mainly associated with symptomatic renal hypertension. The doctrine of hypertension in ophthalmology began to take shape a little more than half a century ago.

Hypertonic disease.

Currently, the study of ophthalmoscopic changes in the fundus is a mandatory element of the examination of patients with hypertension. According to most researchers, modern ophthalmoscopic diagnostics makes it possible to detect changes in the fundus already in the early stages of hypertension in people of all age groups, which can serve the purposes of early diagnosis. U 1/4

In patients with obvious hypertension, ophthalmoscopy reveals a normal fundus.

Fundus changes in hypertension are presented quite widely in the ophthalmological literature. There is a classification by N. Wagener and N. Keith (1939), according to which they distinguish 4

stages of angioretinopathy. The caliber and severity of arteriolar sclerosis, the presence of hemorrhages and exudates are taken into account. This classification deals, first of all, with the types of ophthalmoscopic changes, features of benign and malignant hypertension. In recent years, additions and clarifications have been made to the classification, however, from the point of view of assessing the clinical course of hypertension, it is not very acceptable.

In our country, the classification M. JI has become widespread. Krasnova (1948), which is successfully combined with general clinical classifications of hypertension and reflects the pathogenetic essence of the disease. Three stages of changes in the fundus of the eye have been identified, successively replacing one another: the stage of functional changes in the retinal vessels (hypertensive retinal angiopathy), the stage of organic changes in the retinal vessels (hypertensive retinal angiosclerosis) and the stage of organic changes in the retina and optic nerve (hypertensive retino- and neuroretypopathy).

Hypertensive retinal angiopathy

characterized primarily by narrowing of the retinal arteries, the frequency of this ophthalmoscopic sign reaches 85%

.

In approximately the same percentage of cases, dilatation of the retinal veins is observed. However, this vascular pathology in hypertension manifests itself to varying degrees: according to calimeter data, the dilation of the veins is more pronounced (on average 170

mm) than the narrowing of the retinal arteries (

81

mm).

In this regard, the correct ratio of the caliber of arteries and veins (2:3

) is violated in the direction of increasing this difference (

1:4, 1:5

).

During the period of apgiopathy, uneven caliber and increased tortuosity of the retinal vessels are noted, and a symptom of pathological arteriovenous intersection of the first degree is observed, manifested in a slight narrowing of the vein under the pressure of the artery located on it in the area of intersection. In the central parts of the fundus, a common finding is corkscrew-shaped tortuosity of small venules (Gwist's sign), and in about 1/3

of patients - dissociation of pigment in the area of the macula (Fig. 75).

Changes in retinal vessels found in hypertensive angiopathy are a consequence of hypertonicity and spasm of arterioles, as well as adaptation of blood vessels to new hemodynamic conditions. Symptoms of hypertensive retinal angiopathy, characteristic of the period of functional changes in blood vessels, are inconsistent, especially in the initial phase of the disease. However, their detection indicates significant disturbances in retinal hemodynamics, which has a certain diagnostic and prognostic significance in the clinical assessment of the course of hypertension.

Hypertensive angiosclerosis of the retina

combines a group of symptoms that characterize the stage of organic changes in the retinal vessels. During this period, histomorphologically, hyperplasia of elastic membranes, fibrosis, lipoid infiltration, protein deposits, and areas of necrosis are found in the retinal arteries.

Due to the unevenness and varying intensity of compaction of the arterial wall, hypertensive retinal angiosclerosis is manifested by a large number of ophthalmoscopic signs, polymorphism and originality of the fundus picture.

One of the early phenomena of apgiosclerosis is a symptom of accompanying stripes along the compacted arterial wall; the vessel appears to be double-circuited. With further compaction of the arterial wall, the light reflex reflected by the vessel expands, intensifies and becomes more rigid. This reflex is observed at approximately 50%

cases.

With severe angiosclerosis, the retinal arteries in 2/3

patients narrow (up to

77

microns), their tortuosity and uneven caliber increases. Copper and silver wire symptoms are classic for retinal angiosclerosis. The first of them is explained by plasma impregnation of the wall with lipid deposits, and the second can be observed during organic degeneration of the arterial wall or be of a functional nature, developing as a result of a sharp tonic contraction of the arteries.

Great diagnostic importance is currently attached to the symptom of pathological arteriovenous chiasm (Salus, Relman-Gun symptoms). Distinguish 3

degree of changes: I - “depression of the vein.”

II - an arched bend of the vein at the intersection with the artery, III - a visible break in the vein. In hypertensive angiosclerosis of the retina, the Salus symptom of degree II occurs with a frequency of about 50%

, degree III -

20%

.

Pathology on the part of the optic nerve head is usually associated with the involvement of small vascular branches of this zone in the process of atgiosclerosis and a violation of neuroretinal hemodynamics. U 1/3

In patients with hypertensive angiosclerosis, the optic disc appears pale, monochromatic, with some waxy tint during ophthalmoscopy. In some patients, newly formed vessels and microaneurysms are observed in the area of the optic nerve head (Fig. 76).

Hypertensive retinopathy and neuroretinopathy

in patients with hypertension are a consequence of pathological changes in blood vessels, primarily retinal, as well as hemodynamic changes in the ophthalmic artery basin, which is to some extent associated with profound disturbances in metabolic processes in the body in the late stages of the disease. IN 90%

In some cases, changes in the tissue of the retina and optic nerve are combined with hypertensive angiosclerosis, but the possibility of the development of this pathology against the background of retinal angiopathy in the malignant course of hypertension cannot be excluded.

The most common symptom of hypertensive retinopathy is retinal hemorrhages. In most cases, these are small hemorrhages located in the intergranular layers of the macular and paramacular region ( 30%

), somewhat less often - extensive hemorrhages localized in the layer of nerve fibers in the central parts of the fundus and on the periphery (

20%

).

Retinal swelling is also a manifestation of hypertensive retinopathy. Its typical localization is observed along the vessels in both the non-ripapillary and macular zones.

In the area of the posterior pole of the eye, ophthalmoscopically one can detect dysoric lesions that look like lumps of cotton wool. They can occur with frequency 40%

and are currently regarded as areas of retinal ischemia. In addition, in the central parts of the fundus of the eye, so-called hard exudates often appear - small, bright white, round foci with clear boundaries, located in the outer layers of the retina. They are also an expression of retinal ischemia. In these ischemic zones, deposits of large amounts of lipoids and other fatty substances are observed, which in some cases causes the yellowish tint of “hard exudates”.

The degree and nature of the manifestations of retinopathy may vary. With a relatively benign course of the disease, hypertensive retinopathy may be limited to moderate changes in the central parts of the fundus, i.e., be focal in nature. In the terminal period of the disease, the process in the fundus is diffuse and is often accompanied by the formation of a “star” figure in the area of the macula, which does not always serve as a bad prognostic sign. This applies mainly to those cases when the “star” occurs against the background of severe retinal angiosclerosis and proceeds according to the dry type, i.e., without significant extravasation phenomena.

In most cases (70%

) hypertensive retinopathy is accompanied by pathology of the optic nerve head.

This condition is commonly referred to as hypertensive neuroretinopathy. Changes in the optic nerve are the result of impaired neuroretinal hemodynamics, and in severe cases, increased cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Moderate to significant swelling of the optic disc is possible, with an increase in its size and prominence towards the vitreous body. Sometimes the swelling is limited to only one temporal side of the disc. In approximately 30%

of patients, the optic disc ophthalmoscopically appears pale, monochromatic, with a waxy tint (Fig. 77).

A congested disc in hypertension is a relatively rare phenomenon. It usually accompanies severe and malignant forms of hypertension, mainly in patients with dysfunction of the central nervous system.

Unlike a congestive disc, which occurs with a brain tumor complicated by symptomatic hypertension, in hypertension, a congestive disc is usually combined with significant changes in blood vessels and retinal tissue, i.e., a clinical picture of angiosclerosis and retinopathy. However, differential diagnosis of congestive discs in hypertension and brain diseases is associated with known difficulties and is only possible with a comprehensive examination of patients by a neurosurgeon, therapist and ophthalmologist.

It is known that the ophthalmoscopic picture is an excellent object for studying the vascular system of the whole organism. In this regard, parallel studies of ophthalmological indicators and values characterizing the state of the cardiovascular system provide valuable information. It has been established that the picture of the fundus in hypertension in most patients reflects the level of blood pressure, the value of peripheral resistance to blood flow and, to a certain extent, indicates the state of the contractility of the heart.

In addition to the picture of the fundus, in case of hypertension, an important point in assessing the course of the disease is the study of hemodynamics, the functional state of the visual analyzer, as well as hydrodynamic parameters of the eye.

The study of pressure in the central retinal artery made it possible to establish deep hemodynamic changes in the ophthalmic artery basin, including in patients with hypertension with normal blood pressure in the brachial artery at the time of the study. U 90%

In patients, the diastolic pressure in the central retinal artery is increased (

48-135

mm Hg), while normal values are

31-48

mm Hg. Art. This study acquires particular value in the process of dynamic observation during treatment, since this information indirectly indicates hemodynamics in the internal carotid artery system, which has a certain autonomy.

Rheoophthalmography in patients with hypertension also indicates changes in the hemodynamics of the ciliary body, progressing as the disease develops, and a decrease in the blood supply of the ciliary body is usually detected against the background of changes in the elastic properties of the wall of its numerous vessels.

With hypertension, the hydrodynamic parameters of the eye change. Almost 70%

patients with normal levels of ophthalmotonus tend to have impaired circulation of intraocular fluid. As the disease progresses, this is manifested by a decrease in the production and filtration of chamber moisture.

It is no coincidence that among patients with suspected glaucoma, a significant percentage are patients with hypertension. Overt glaucoma in this category of patients is also detected with a higher frequency, reaching 2,5—8,5%

, with the prevalence of glaucoma averaging about

1%

in people over

40

years of age. Currently, patients with hypertension are classified as a group of people at increased risk of glaucoma.

However, as clinical practice shows, an increase in blood pressure in patients with glaucoma has a beneficial effect on the blood supply to the eye as a whole due to an increase in pulse volume.

In the literature there are indications of the presence of correlations between hemo- and hydrodynamics in patients with hypertension. This refers to blood circulation indicators, both local, i.e., the eyeball, and the body as a whole. In practical terms, it is necessary to keep in mind the possibility of a combination of a hypertensive crisis and an acute attack of glaucoma.

Some subjective similarity of these emergency conditions sometimes causes diagnostic errors, leading to incorrect treatment tactics. In patients with hypertensive crisis, it is necessary to evaluate ophthalmotonus, and in case of an acute attack of glaucoma, measure blood pressure.

Changes in visual functions in hypertension are very diverse. However, in terms of pathogenesis they cannot be classified as general specific changes and should be regarded as the result of damage to the eyeball itself and the visual analyzer as a whole.

The field of view narrows most often concentrically at 10— 20

°C even with a relatively normal ophthalmoscopic picture. In the presence of foci of softening and hemorrhages in various parts of the brain, hemianopsia appears, differing in a variety of forms. Along with the limitation of visual fields, careful examination should reveal an increase in the blind spot. In patients with hypertension, dark adaptation is reduced and color sensitivity is impaired, especially to red, green and blue colors.

Symptomatic hypertension.

Symptomatic renal arterial hypertension is characterized by significant changes in the fundus of the eye. In general, they are similar to those that occur in hypertension, since the elements that form the ophthalmoscopic picture are practically the same (angiopathy, hemorrhages, transudative component).

However, the fundus of the eye in hypertension and renal hypertension cannot be called absolutely identical. The severity of certain ophthalmoscopic signs and their combinations create a unique picture of the fundus, which makes it possible, with a certain degree of categoricalness, to make a differential diagnosis between these two diseases, which are often clinically very similar, characterized by increased blood pressure.

When describing the ophthalmoscopic picture in patients with symptomatic renal hypertension, the classification scheme that has been proposed for hypertension is usually used. However, it must be pointed out that with renal hypertension there may be stages, a sequence of changes in the fundus, as has been established for hypertension.

This fact is explained by the lack of stages in the clinical course of the underlying disease, which led to increased blood pressure. The ophthalmoscopic picture in patients with renal diseases indicates the degree of pathology of the retinal vessels, its tissue and the optic nerve.

Hypertensive (renal) retinal angiopathy

characterized primarily by a sharp narrowing of the retinal arteries in most patients (82%

) with simultaneous moderate expansion of the veins (

50%

). Thus, in contrast to hypertension, venous pathology in the fundus in hypertensive renal angiopathy is less pronounced and the main ophthalmoscopic picture in renal hypertension is changes in the arteries; they are sharply narrowed, but their caliber appears uniform and their stroke is straight. During this period, biomicroscopically one can detect slight swelling of the optic nerve head and retina in the peripapillary zone, which indicates extravasation phenomena typical of renal hypertension (Fig. 78).

Apgiosclerosis of the retina

with symptomatic renal hypertension is extremely rare, only in 7—10%

sick.

Ophthalmoscopic signs characterizing the phenomena of retinal angiosclerosis practically do not differ from those in hypertension. A feature of retinal angiosclerosis in kidney diseases is a sharp narrowing of the retinal arteries in 100%

of cases. This is a rather pathognomonic sign, since in young patients suffering from renal hypertension, the influence of the involution factor is usually excluded.

A fairly typical sclerotic sign is also the presence in the outer layers of the retina of shiny, small foci with iridescent colors. This is very typical for patients with the nephrotic form of chronic glomerulonephritis, occurring with hypercholesterolemia.

Hypertensive (renal) retinopathy and neuroretinopathy

seems in many ways different from a similar pathology associated with hypertension. The main distinguishing feature is the fact that in patients with renal hypertension, retinopathy usually develops against the background of retinal angiopathy, and angiosclerosis is an extremely rare phenomenon. Total 20—25%

In patients with renal hypertension, angiosclerosis is observed with a picture of retinopathy, while in hypertension the frequency of angiosclerosis reaches

90%

.

The next characteristic sign of renal hypertension is pronounced transudative syndrome. It manifests itself in a greater degree of retinal edema compared to hypertension. The edematous component is usually localized in the peripapillary zone, the macula area and along large vascular branches. In rare cases, with acute and severe renal hypertension, retinal edema can be almost total.

Very typical for this pathology are “soft exudates”, which are cotton-wool-like foci located in the central parts of the fundus. “Hard exudates” in the form of yellowish, small, round, millet-like lesions are found in almost half of patients with renal retinopathy, and are usually located between the optic disc and the macula area.

When present in significant quantities, “solid exudates” can form a star shape. Hemorrhagic syndrome is not very characteristic of renal retinopathy, while in hypertension, hemorrhages constitute the main element of the ophthalmoscopic picture of retinopathy.

Neuropathy of renal origin is expressed by swelling of the optic disc of varying degrees, and the color of the disc is pallor, hemorrhages into the disc tissue are uncommon. Such changes are the result of impaired hemodynamics and permeability of the walls of small vessels in this area. Among patients with hypertensive renal neuroretinopathy, there is a fairly large percentage of people with a “star” shape in the macula area ( 10%

). The “star” is formed from “soft” and “hard” exudates and tends to reverse development with a favorable course of hypertension and underlying kidney disease (Fig. 79, 80).

Thus, despite some differences in the ophthalmoscopic picture in patients with symptomatic renal hypertension and essential hypertension, the differential diagnosis of these two forms of hypertension is extremely difficult, and during the period of retinal angiopathy it is hardly possible at all. Retinal angiosclerosis often indicates the presence of hypertension. Only neuroretinopathy has significant differences between these forms of hypertension.

However, in each case, the condition of the fundus should be assessed individually, taking into account the patient’s age, duration of the disease, and remembering that fundus examination is only an element of a comprehensive examination of the body’s vascular system.

It has now been established that the ophthalmoscopic picture of symptomatic renal hypertension depends, first of all, on the clinical form of kidney pathology that led to hypertensive syndrome.

Chronic diffuse glomerulonephritis

This is especially clearly seen in cases of chronic diffuse glomerulonephritis a. In its hypertensive form, when the main symptom is an increase in blood pressure, in 50%

cases, hypertensive (renal) retinopathy and neuroretinopathy of varying severity are observed. The nephrogenic form of chronic glomerulonephritis is characterized by normal blood pressure and severe urinary syndrome; the condition of the fundus is normal.

The malignant variant of the course of chronic glomerulonephritis, especially complicated by chronic renal failure, is characterized by particularly severe pathology of the fundus. U 50%

patients have a clinical picture of retinopathy, including a “star” figure in the macula area, which in this case is a poor prognostic sign. The “star” has a pronounced transudative character, its radiance has a grayish tint. In the latent form of chronic glomerulonephritis, changes in the fundus of the eye are reduced only to the presence of angiopathy or are absent.

Chronic pyelonephritis

often accompanied by arterial hypertension and in some cases ends in uremia. Changes in the fundus are characterized mainly by the same signs that are typical for the hypertensive form of chronic glomerulonephritis. However, neuroretinopathy in chronic pyelonephritis ( 30%

) cases are less common. In addition, retinal hemorrhages, combined with the presence of moderate arteriolar sclerosis, are typical for pyelonephritis.

Non-vascular kidney diseases

accompanied by impaired renal circulation and, in connection with this, moderate hypertension, are characterized by minimal changes in the fundus of the eye, even with a relatively long duration of the disease. In patients with developmental anomalies of the kidneys and ureter, kidney stones, hydronephrosis, nephroptosis and other changes, hypertensive renal angiopathy of the retina is usually observed ( 60%

cases) and often a normal fundus.

Occlusive renal hypertension

has not been properly reflected in the ophthalmological literature, despite the fact that it occurs with pronounced changes in the fundus and 20,8%

cases has a malignant course.

Stenosis of the renal artery can be congenital or acquired. Among the features of the clinical course, the acute onset of the disease, the young age of the patients, persistent hypertension and the absence of changes in the urine should be noted. The fundus of the eye in this category of patients is characterized by severe changes: in 70%

of cases, neuroretinopathy is diagnosed, usually without signs of angiosclerosis, but with a large amount of moist and “hard” exudates. With a favorable course of the disease, which is usually ensured by surgical treatment, a fairly rapid reverse development of neuroretinopathy and complete restoration of visual functions are observed.

Toxicosis of the second half of pregnancy

Renal arterial hypertension includes hypertension that occurs during toxicosis in the second half of pregnancy. There are common pathogenetic and clinical signs characteristic of nephropathy in pregnancy and chronic glomerulonephritis. The fundus picture in pregnancy nephropathy also has great similarities with the pathology characteristic of chronic glomerulonephritis.

Depending on the severity of toxicosis, hypertensive retinal angiopathy and various types of renal neuroretinopathy may be observed. In general, but according to various authors, the percentage of fundus changes in late toxicosis of pregnant women reaches 30—90

.

Changes in the fundus are often the first signs of a pathological condition during pregnancy, and neuroretinopathy indicates severe toxicosis, requiring active general therapy, and sometimes termination of pregnancy.

Thus, with symptomatic renal hypertension, there is a clearly visible connection between the nature and degree of fundus changes with the clinical form of kidney pathology, which leads to increased blood pressure.

The results of comparison of the severity of the ophthalmoscopic picture, indicators of general and renal hemodynamics and the functional state of the kidneys show the dependence of ocular pathology in renal hypertension primarily on the height of blood pressure.

The parallelism between the severity of ophthalmoscopic changes and peripheral resistance to blood flow, which approximately characterizes the size of the total lumen of the arterioles of the whole organism, is also clearly expressed. Neuroretinopathy in most patients with renal hypertension is combined with significant impairment of renal hemodynamics.

Symptomatic arterial hypertension includes clinical situations associated with damage to large vessels. Among those that are reflected in the ophthalmological literature and have certain ophthalmological symptoms, we can name Takayasu’s disease and coarctation of the aorta.

Panarteritis of the aorta and its branches

(Takayasu's disease - pulseless disease, arteritis of young women) leads to an increase in blood pressure of approximately 50%

cases. Hypertension is to a certain extent caused by cerebral ischemia and the renal ischemic factor. The disease is characterized as a kind of inflammatory-allergic process, close to collagenosis. Eye damage is observed in half of the patients.

This disease and ophthalmological symptoms were first described by the Japanese ophthalmologist M. Takayasu in 1908. He noted the classic triad of symptoms in the patient 21

years: absence of pulse on the radial artery, cataracts and arteriovenous anastomoses around the optic nerve head. Subsequently, reports appeared in the literature about the presence of vasodilatation of the conjunctiva and episclera, clouding of the cornea, mydriasis, and iris atrophy in this disease.

A common change in the lens is cataract, in which opacification usually occurs in the nuclear zone. In the fundus there is a picture of angiopathy with narrowing of the arteries, dilation of the veins and large tortuosity of the vessels; microaneurysms, arteriovenous anastomoses, periphlebitis, proliferating retinitis, hemorrhages in the retina and vitreous body are possible.

The variety of eye symptoms is the result of the fact that the disease is multidisciplinary: it is inflammatory in nature, accompanied by arterial hypertension and, in addition, cerebral ischemia.

Panarteritis of the aorta and its branches can cause a complicated clinical situation in the retinal vessels and optic nerve. Young women with this pathology experience acute arterial and venous obstruction of the retinal vessels, as well as the vessels of the optic nerve. Such patients require active complex therapy, including steroid hormones, antibiotics and anticoagulants.

Coarctation of the aorta

is one of the congenital malformations of large vessels. The disease is accompanied by regional hypertension of the upper half of the body. A very peculiar picture is observed in the fundus, due to the fact that under conditions of high blood pressure, often systolic, many retinal vessels that do not function normally are filled with blood.

This leads to a bright coloration of the entire fundus of the eye, in particular the optic disc, the boundaries of which are sometimes difficult to distinguish. The arteries and veins of the retina are extremely tortuous and full of blood. Hemorrhages and transudative elements are atypical for the ophthalmoscopic picture. The vessels of the conjunctiva and episclera are also characterized by great tortuosity and congestion. The capillaries of the limbus have the shape of the Greek letter “omega” and are also significantly expanded.

Ophthalmological characteristics of other forms of symptomatic arterial hypertension, caused, in particular, by sclerosis, blood diseases, pathology of the endocrine and nervous systems, are presented in the relevant sections of the manual.

Article from the book: Therapeutic ophthalmology | Krasnov M.L.; Shulpina N.B..